Pick Up

1402. Commodity Market Intervention in a Divided World

1402. Commodity Market Intervention in a Divided World

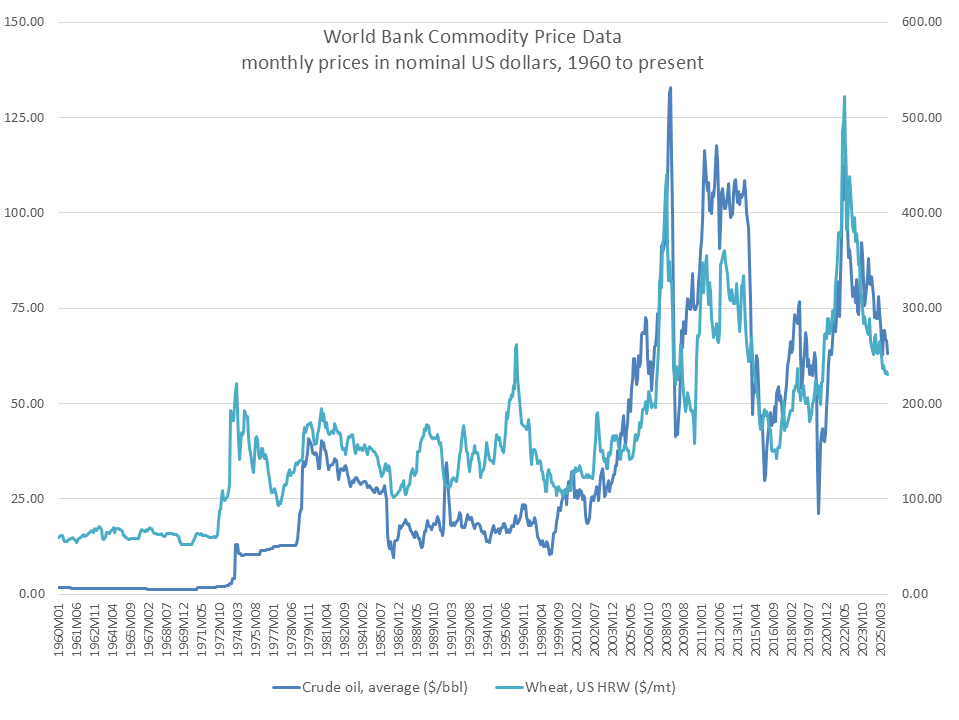

Commodity price volatility and the associated risks to energy and food security have rekindled interest in market intervention for commodity supply management. An article from the Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) looks back at attempts at international commodity agreements over the past century and points out the limitations of market intervention's effectiveness.

Recent calls for intervention in energy, metals, and food markets are reminiscent of the international commodity agreements (ICAs) of the past. In the 20th century, approximately 40 ICAs were concluded for metals such as copper and tin, agricultural raw materials such as rubber and wool, and foodstuffs such as wheat, sugar, and coffee. While pre-World War II agreements were typically concluded solely by producers, post-World War II agreements typically involved both exporting and importing countries seeking to influence prices through production quotas and inventory management. These post-war agreements covered approximately 65% of the global production of the relevant commodities. The oil market has similarly had a marked history, dating back to the 19th century, of producer intervention to manage surplus supplies. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), established in 1960, is the only commodity agreement still in operation.

Wheat is the only commodity included in the AMIS analysis that has operated under an international commodity agreement, and its experience highlights the difficulties of such market stabilization efforts. The first attempt, the 1933 International Wheat Agreement, brought together nine exporting and 12 importing countries to coordinate export and import quotas and manage planted area. However, weak monitoring mechanisms and the emergence of global bumper harvests caused the agreement to collapse within a year. A second initiative, negotiated in 1949, established a multilateral contract system under which exporting countries committed to a maximum selling price and importing countries to a minimum purchasing price. This agreement was renewed multiple times, but failed to achieve lasting price stability. Its effectiveness was further limited by its small membership. Member countries accounted for approximately two-thirds of global wheat trade but less than one-fifth of global production. In 1995, the Grains Trade Convention was introduced, covering a broader range of countries, but its objectives shifted from price stability to promoting cooperation, market transparency, and free trade.

A key lesson learned from a century of ICAs is that markets tend to adjust more quickly than institutions can manage. Many agreements were undermined by inherent contradictions. Policies aimed at stabilizing or raising prices in favor of producers ultimately triggered reactions that undermined the agreement itself. Rising prices encouraged innovation, extraneous new production, quota violations, and consumer substitution, contributing to the collapse of ICAs like those for coffee, natural rubber, and tin. Efforts to protect price bands through stockpiling exposed the limits of resisting underlying market forces. Postwar agreements that attempted to balance the interests of producers and consumers largely failed to stabilize prices over the long term. While resilient, OPEC faced similar pressures and had to adapt, moving from fixed to market pricing, adopting flexible production quotas, and expanding cooperation through OPEC+. However, new sources of supply and changing demand patterns have increasingly constrained its influence. OPEC-led price hikes in the 1970s spurred large-scale new production in Alaska, the Gulf of Mexico, and the North Sea in the 1980s, and the oil boom since 2000 has fueled the rise of U.S. shale oil and Canadian oil sands. At the same time, structural changes in global energy markets—declining oil intensity as a percentage of GDP, rising shares of natural gas and renewable energy, and slowing oil demand growth—make quota management increasingly challenging.

Although commodity agreements have a poor track record, coordinated international action can be effective during severe crises. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, OPEC+ production cuts, combined with voluntary production cuts by other producers, helped stabilize crude oil prices amid a historic collapse in demand. In food markets, strategic grain reserves can support crisis management and emergency preparedness, but their role should be limited to short-term stabilization rather than long-term price control. Similarly, knowledge sharing and data transparency are essential to guide policy responses and promote market stability during periods of stress.

In summary, while temporary measures during acute disruptions can mitigate price volatility, there are few examples of successful long-term price control schemes. A sustainable and stable supply of goods is likely to emerge from resilient strategies that support diversification, foster innovation, improve data transparency, and rely on market-based pricing mechanisms.

Contributor: IIYAMA Miyuki, Information Program