Pick Up

1385. Trying to Make a Case in Africa: “Let the Fields Rest and Enrich the Farmers!”

1385. Trying to Make a Case in Africa: “Let the Fields Rest and Enrich the Farmers!”

Economic Development Doesn't Eliminate Hunger

What comes to mind when you think of Africa? “Incredible momentum for development” or “Poverty and severe hunger” – completely different answers, but both are correct. Africa's economic growth rate exceeds the global average. With its large young population and continuous population growth, it is considered one of the world's most promising growth markets. Yet, due to climate change, rising global food prices, and prolonged conflicts, it is also the region where the most people suffer from hunger worldwide. As the population grows, the need to consistently produce large amounts of food increases. However, Africa's agricultural productivity remains lower than in other parts of the world. There are several reasons for this. For example, climate change, limited use of new technologies, difficulty accessing loans, inadequate infrastructure such as land, markets, and roads, and insufficient information dissemination. Among these, one particularly significant cause is “soil degradation.”

Even Fields Need a Break!

In ancient Africa, a practice called “fallow” allowed fields to rest for a period, helping the soil recover. However, as populations grew and land was divided among family members, many farmers lost the luxury of resting their fields. Without rest, the soil's ability to hold nutrients and moisture declines, gradually reducing crop yields. Furthermore, poor soil absorbs fertilizer less effectively, leading farmers to feel that “using fertilizer is just a loss.” Consequently, they apply less fertilizer, creating a vicious cycle where productivity continues to fall. This problem is particularly severe in the arid regions of West Africa. To prevent such soil degradation, various techniques have been developed: mulching with grass or crop residues (stems and leaves left in the field), ridge planting, stone placement, and a technique called “zai,” which involves digging holes and filling them with compost. However, these methods require significant money and labor, and it takes time for their effects to become apparent, making widespread adoption difficult.

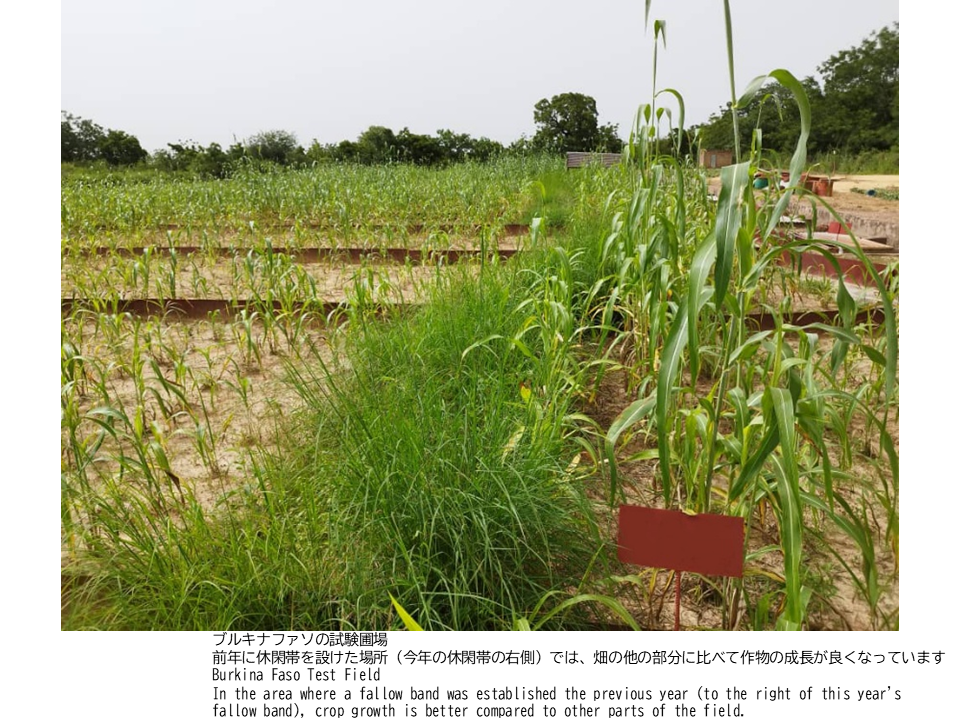

The “Fallow Band System” Requiring Neither Money nor Labor

Therefore, the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS) has developed a new technique to prevent soil degradation called the “Fallow Band System.” This method involves creating a 1-meter-wide “fallow band” (a band of land left untouched) every 15 meters within the field. These fallow bands are positioned to block the flow of rainwater. As a result, soil layers closer to the surface contain more nutrients. The most nutrient-rich soil, washed down by rain, accumulates in the fallow band. The following year, the fallow band is moved slightly uphill. By shifting the fallow band annually in this way, soil degradation is prevented. Furthermore, from the second year onward, cultivation can also be done in the previous year's fallow band, which has accumulated nutrients, potentially increasing yields. Moreover, it requires little money or labor. The effectiveness of this technique has been proven through six years of field trials locally. However, in the first year after establishing the fallow band, the harvest in that area inevitably decreases by about 6%. Unfortunately, because the decline in yield due to soil degradation occurs gradually, farmers may find it difficult to notice and may be reluctant to take countermeasures. For this reason, it is possible that this technique may not spread among farmers. Figuring out what to do about this is my role.

Aiming for Adoption in Burkina Faso

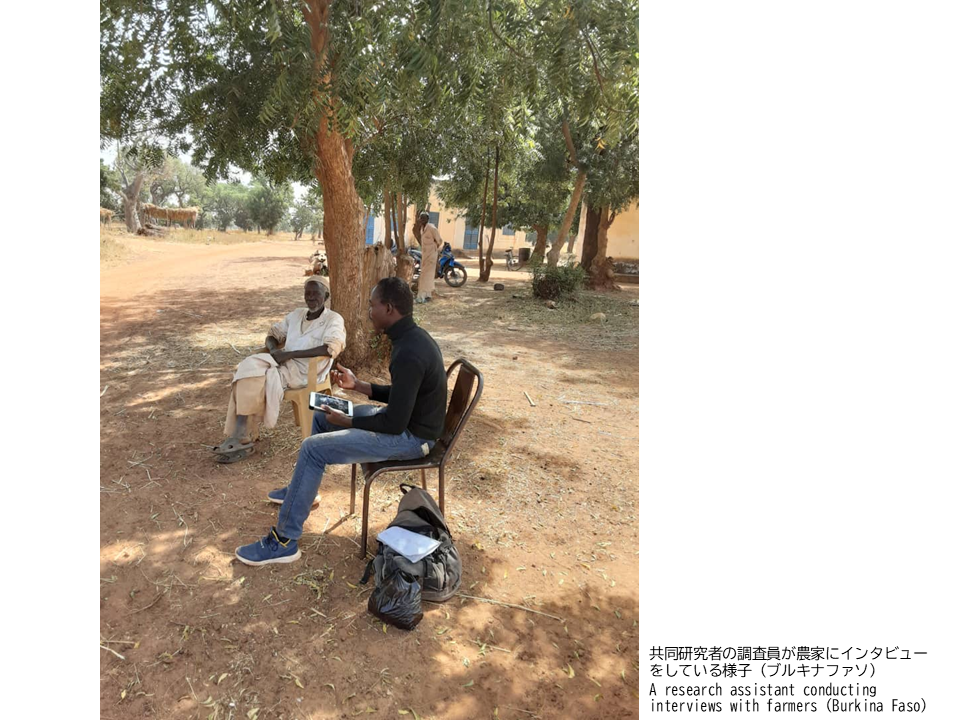

I conduct research in the field of agricultural economics. I interview farmers to collect data on agricultural production and household finances, then use economic and statistical models to investigate questions like “Which technologies and systems effectively boost agricultural productivity?” and “How can agricultural technologies be effectively disseminated?” Currently, in Burkina Faso, I'm researching how to effectively spread this “fallow band system” among farmers. People often find it difficult to take immediate action even when future disadvantages seem likely. This research incorporates behavioral economics, a field that recently produced a Nobel laureate in Economics. Specifically, we conduct “technical training” designed to make farmers more likely to act against distant disadvantages. This falls under the field of human economic experiments. For such research, direct dialogue between researchers and farmers on-site is essential. However, a coup in Burkina Faso in 2022 made it impossible to access the field. Therefore, in collaboration with local co-researchers, we are conducting research using innovative approaches, including IT tools such as CAPI (Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing). We intend to continue this research, aiming to contribute, even in a small way, to protecting Africa's soil, ensuring stable food production, increasing farmers' incomes, and reducing hunger and poverty.

(Photo) We conducted farmer interviews to explore the potential for promoting fallow band systems in Senegal (second from right is the author).

Contributor: MURAOKA Rie, Social Sciences Division