Pick Up

1432. Elucidating the Pathways of Change in Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emissions

1432. Elucidating the Pathways of Change in Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The food system is a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These emissions are typically categorized by physical source: land-use change (51%), enteric fermentation and manure management (26%), soil and pasture management (11%), and rice cultivation (8%). Various scenarios suggest that limiting global warming to 2–3°C requires significant GHG emission reductions from the agricultural sector.

Discussions regarding GHG emission reductions in agriculture have primarily focused on "decoupling" pathways, which aim to reduce emissions while maintaining production growth. Conceptually, emissions in the agricultural sector are unwanted by-products of production and cannot be freely removed or disposed of. Decoupling strategies can be broadly divided into those that reduce emissions within the scope of existing technology and those that improve agricultural productivity. The former focus on abatement costs and compensation to encourage farmers to adopt best management practices, while the latter focus on research and development (R&D) costs to achieve productivity gains.

While existing research highlights the role that improving agricultural productivity plays in reducing emissions, the role of inputs other than land has received relatively little attention. However, agriculture is not solely dependent on land. The impact of changes in the levels and productivity of other inputs, such as labor, capital, and raw materials, on decoupling has yet to be fully explored.

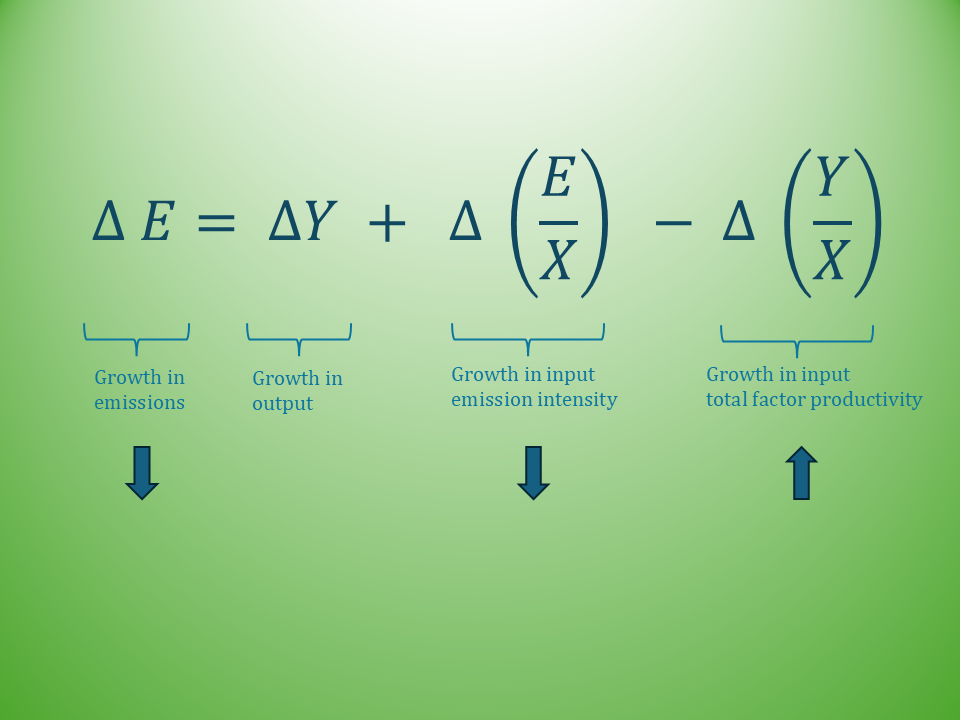

The paper, published in Science Advances, decomposed agricultural GHG emissions growth (△E) into three components: production (△Y), emissions per input (△E/X), and output per input (△Y/X), or total factor productivity (TFP), and quantified the contributions of these components using official country-level data.

Global agricultural production has more than tripled (up 270%) since 1961, averaging approximately 2.2% annual growth. Global GHG emissions from the agricultural sector have also increased over the same period, but at a much slower rate than production growth. Global emissions growth declined from approximately 1.6% per year in the 1960s to approximately 0.28% per year in the 2010s. While emissions trends since 1961 do not fully capture agricultural GHG emissions, the slower growth in emissions compared to output growth is a sign of decoupling, reflected in a decline in output-emissions intensity over time. While output growth was the primary driver of emissions growth, TFP growth was the primary driver of emissions reductions. The relative role of TFP growth in these reductions was greatest in high-income countries (1.19% per year), nearly offsetting the contribution of output growth (1.27% per year), leading to stagnant emissions (0.02% per year). Meanwhile, in lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries, declines in input emission intensity have played a relatively larger role in emissions reductions compared to other income groups. In contrast, TFP growth was slowest in low-income countries, primarily located in Africa.

The study further suggests that technological change that improves land productivity is more closely associated with reduced emissions intensity and decarbonization than technological change that improves labor productivity. Technological change, such as mechanization, increases labor productivity but does not necessarily alter biophysical processes that generate GHGs as by-products. In contrast, technologies that increase land productivity, such as improved fertilizer use, contribute to decoupling by increasing production and lowering emissions intensity.

(Reference)

Ariel Ortiz-Bobea et al., Unpacking the growth of global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, Science Advances (2026). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aeb8653

Contributor: IIYAMA Miyuki, Information Program